Signal Boosting

The new release of Preact Signals brings significant performance updates to the foundations of the reactive system. Read on to learn what kinds of tricks we employed to make this happen.

We recently announced new versions of the Preact Signals packages:

- @preact/signals-core 1.2.0 for the shared core functionality

- @preact/signals 1.1.0 for the Preact bindings

- @preact/signals-react 1.1.0 for the React bindings

This post will outline the steps that we took to optimize @preact/signals-core. It's the package that acts as a base for the framework specific bindings, but can also be used independently.

Signals are the Preact team's take on reactive programming. If you want a gentle introduction on what Signals are all about and how they tie in with Preact, the Signals announcement blog post has got you covered. For a deeper dive check out the official documentation.

It should be noted that none of these concepts are invented by us. Reactive programming has quite a history, and has already been popularized widely in the JavaScript world by Vue.js, Svelte, SolidJS, RxJS and too many others to name. Kudos to all of them!

A Whirlwind Tour of the Signals Core

Let's start with an overview of the fundamental features in the @preact/signals-core package.

The code snippets below use functions imported from the package. The import statements are shown only when a new function is brought into the mix.

Signals

Plain signals are the fundamental root values which our reactive system is based on. Other libraries might call them, for example, "observables" (MobX, RxJS) or "refs" (Vue). The Preact team adopted the term "signal" used by SolidJS.

Signals represent arbitrary JavaScript values wrapped into a reactive shell. You provide a signal with an initial value, and can later read and update it as you go.

import { signal } from '@preact/signals-core';

const s = signal(0);

console.log(s.value); // Console: 0

s.value = 1;

console.log(s.value); // Console: 1By themselves signals are not terribly interesting until combined with the two other primitives, computed signals and effects.

Computed Signals

Computed signals derive new values from other signals using compute functions.

import { signal, computed } from '@preact/signals-core';

const s1 = signal('Hello');

const s2 = signal('World');

const c = computed(() => {

return s1.value + ' ' + s2.value;

});The compute function given to computed(...) won't run immediately. That's because computed signals are evaluated lazily, i.e. when their values are read.

console.log(c.value); // Console: Hello WorldComputed values are also cached. Their compute functions can potentially be very expensive, so we want to rerun them only when it matters. A running compute function tracks which signal values are actually read during its run. If none of the values have changed, then we can skip recomputation. In the above example, we can just reuse the previously calculated c.value indefinitely as long as both a.value and b.value stay the same. Facilitating this dependency tracking is the reason why we need to wrap the primitive values into signals in the first place.

// s1 and s2 haven't changed, no recomputation here

console.log(c.value); // Console: Hello World

s2.value = 'darkness my old friend';

// s2 has changed, so the computation function runs again

console.log(c.value); // Console: Hello darkness my old friendAs it happens, computed signals are themselves signals. A computed signal can depend on other computed signals.

const count = signal(1);

const double = computed(() => count.value * 2);

const quadruple = computed(() => double.value * 2);

console.log(quadruple.value); // Console: 4

count.value = 20;

console.log(quadruple.value); // Console: 80The set of dependencies doesn't have to stay static. The computed signal will only react to changes in the latest set of dependencies.

const choice = signal(true);

const funk = signal('Uptown');

const purple = signal('Haze');

const c = computed(() => {

if (choice.value) {

console.log(funk.value, 'Funk');

} else {

console.log('Purple', purple.value);

}

});

c.value; // Console: Uptown Funk

purple.value = 'Rain'; // purple is not a dependency, so

c.value; // effect doesn't run

choice.value = false;

c.value; // Console: Purple Rain

funk.value = 'Da'; // funk not a dependency anymore, so

c.value; // effect doesn't runThese three things - dependency tracking, laziness and caching - are common features in reactivity libraries. Vue's computed properties are one prominent example.

Effects

Computed signals lend themselves well to pure functions without side-effects. They're also lazy. So what to do if we want to react to changes in signal values without constantly polling them? Effects to the rescue!

Like computed signals, effects are also created with a function (effect function) and also track their dependencies. However, instead of being lazy, effects are eager. The effect function gets run immediately when the effect gets created, and then again and again whenever the dependency values change.

import { signal, computed, effect } from '@preact/signals-core';

const count = signal(1);

const double = computed(() => count.value * 2);

const quadruple = computed(() => double.value * 2);

effect(() => {

console.log('quadruple is now', quadruple.value);

// Console: quadruple value is now 4

});

count.value = 20; // Console: quadruple value is now 80These reactions are triggered by notifications. When a plain signal changes, it notifies its immediate dependents. They in turn notify their own immediate dependents, and so on. As is common in reactive systems, computed signals along the notification's path mark themselves to be outdated and ready be recomputed. If the notification trickles all the way down to an effect, then that effect schedules itself to be run as soon as all previously scheduled effects have finished.

When you're done with an effect, call the disposer that got returned when the effect was first created:

const count = signal(1);

const double = computed(() => count.value * 2);

const quadruple = computed(() => double.value * 2);

const dispose = effect(() => {

console.log('quadruple is now', quadruple.value);

// Console: quadruple value is now 4

});

dispose();

count.value = 20; // nothing gets printed to the consoleThere are other functions, like `batch`, but these three are the most relevant to the implementation notes that follow.

Implementation Notes

When we set out to implement more performant versions of the above primitives, we had to find snappy ways to do all the following subtasks:

- Dependency tracking: Keep track of used signals (plain or computed). The dependencies may change dynamically.

- Laziness: Compute functions should only run on demand.

- Caching: A computed signal should recompute only when its dependencies may have changed.

- Eagerness: An effect should run ASAP when something in its dependency chain changes.

A reactive system can be implemented in a bajillion different ways. The first released version of @preact/signals-core was based on Sets, so we'll keep using that approach to contrast and compare.

Dependency Tracking

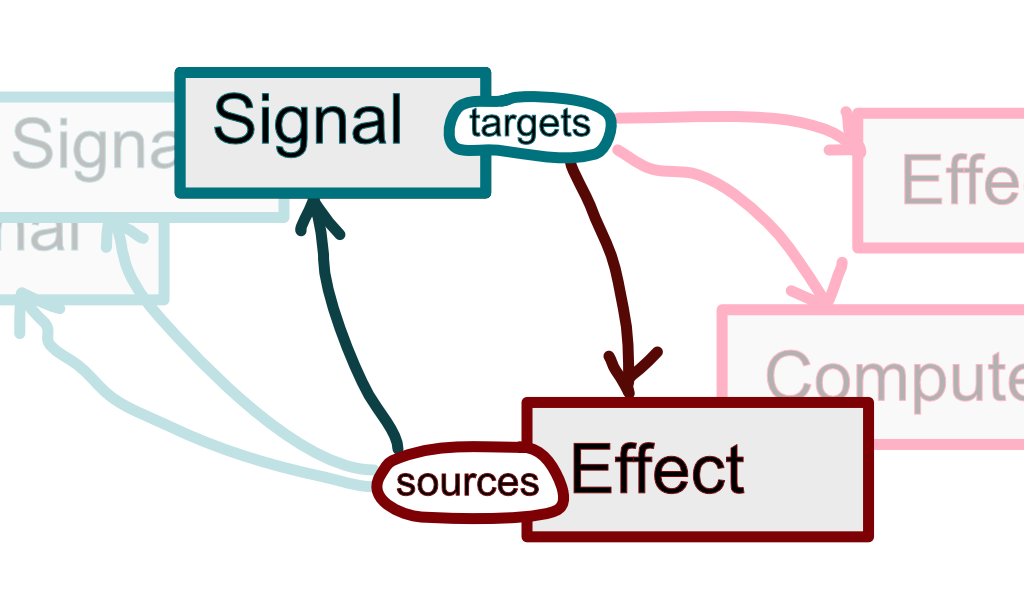

Whenever a compute/effect function starts evaluating, it needs a way to capture signals that have been read during its run. For that the computed signal or effect sets itself as the current evaluation context. When a signal's .value property is read, it calls a getter. The getter adds the signal as a dependency, source, of the evaluation context. The context also gets added as a dependent, target, of the signal.

In the end signals and effects always have an up-to-date view of their dependencies and dependents. Each signal can then notify its dependents whenever its value has changed. Effects and computed signals can refer to their dependency sets to unsubscribe from those notifications when, say, an effect is disposed.

The same signal may get read multiple times inside the same evaluation context. In such cases it would be handy to do some sort of deduplication for dependency and dependent entries. We also need a way to handle changing sets of dependencies: to either rebuild the set of dependencies on every run or incrementally add/remove dependencies/dependents.

JavaScript's Set objects are a good fit for all that. Like many other implementations, the original version of Preact Signals used them. Sets allow adding and removing items in constant O(1) time (amortized), as well as iterating through the current items in linear O(n) time. Duplicates are also handled automatically! It's no wonder many reactivity systems take advantage of Sets (or Maps). The right tool for the job and all that.

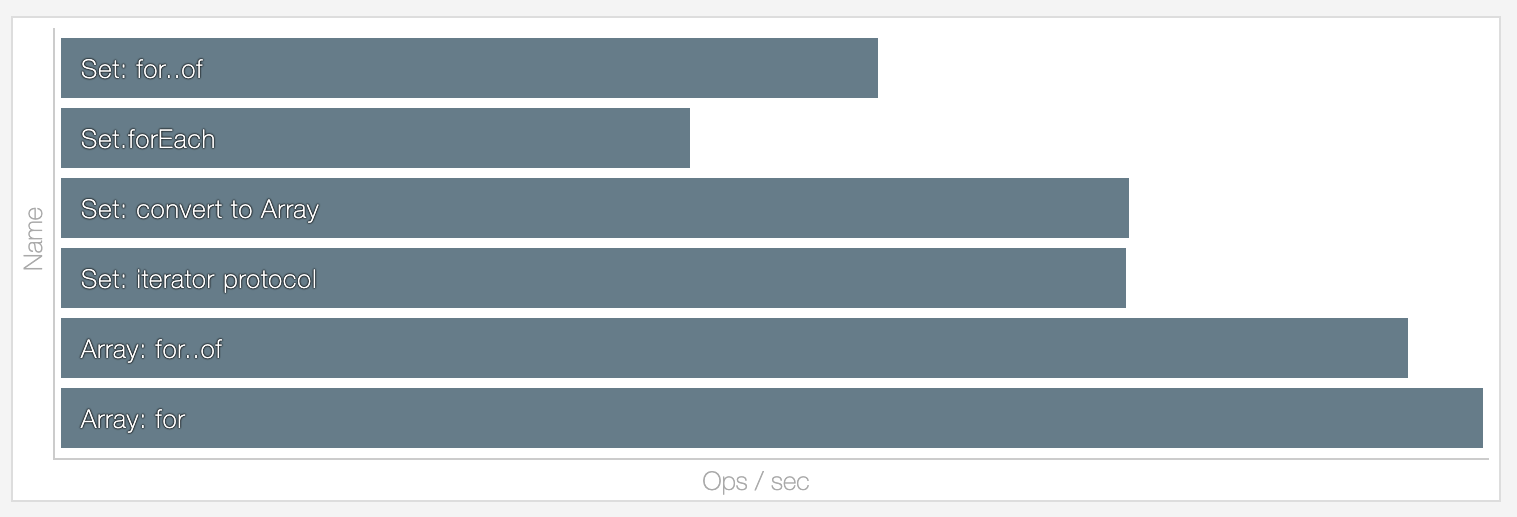

However, we were wondering whether there are some alternative approaches. Sets can be relatively expensive to create, and at least computed signals may need two separate Sets: one for dependencies and one for dependents. Jason was being a total Jason again and benchmarked how Set iteration fares against Arrays. There will be lots of iterating so it all adds up.

Sets also have the property they're iterated in insertion order. Which is cool - that's just what we need later when we deal with caching. But there's the possibility that the order doesn't always stay the same. Observe the following scenario:

const s1 = signal(0);

const s2 = signal(0);

const s3 = signal(0);

const c = computed(() => {

if (s1.value) {

s2.value;

s3.value;

} else {

s3.value;

s2.value;

}

});Depending on s1 the order of dependencies is either s1, s2, s3 or s1, s3, s2. Special steps have to be taken to keep Sets in order: either remove and then add back items, empty the set before a function run, or create a new set for each run. Each approach has the potential to cause memory churn. And all this just to account for the theoretical, but probably rare, case that the order of dependencies changes.

There are multiple other ways to deal with this. For example numbering and then sorting the dependencies. We ended up exploring linked lists.

Linked Lists

Linked lists are often considered quite primitive, but for our purposes they have some very nice properties. If you have a doubly-linked list nodes then the following operations can be extremely cheap:

- Insert an item to one end of the list in O(1) time.

- Remove a node (for which you already have a pointer) from anywhere in the list in O(1) time.

- Iterate through the list in O(n) time (O(1) per node)

Turns out that these operations are all we need for managing dependency/dependent lists.

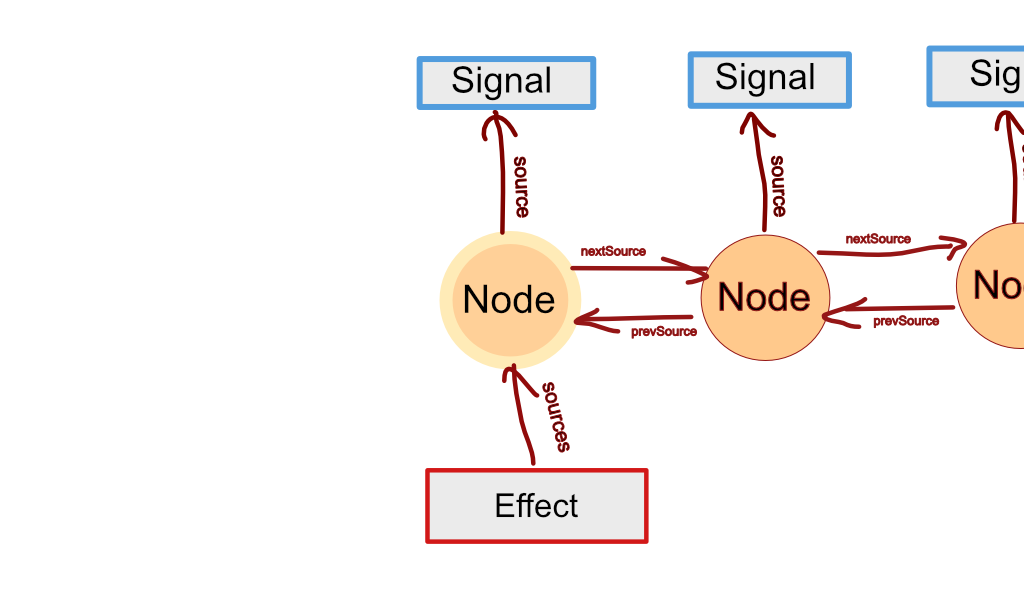

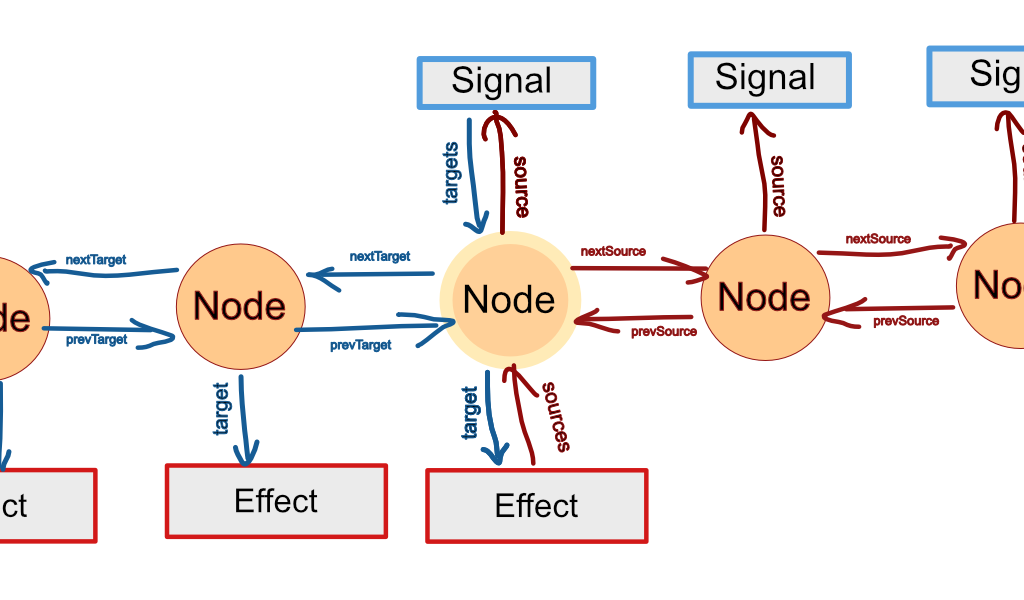

Let's start by creating a "source Node" for each dependency relation. The Node's source attribute points to the signal that's being depended on. Each Node has nextSource and prevSource properties pointing to the next and previous source Nodes in the dependency list, respectively. Effects or a computed signals get a sources attribute pointing to the first Node of the list. Now we can iterate through the dependencies, insert a new dependency, and remove dependencies from the list for reordering.

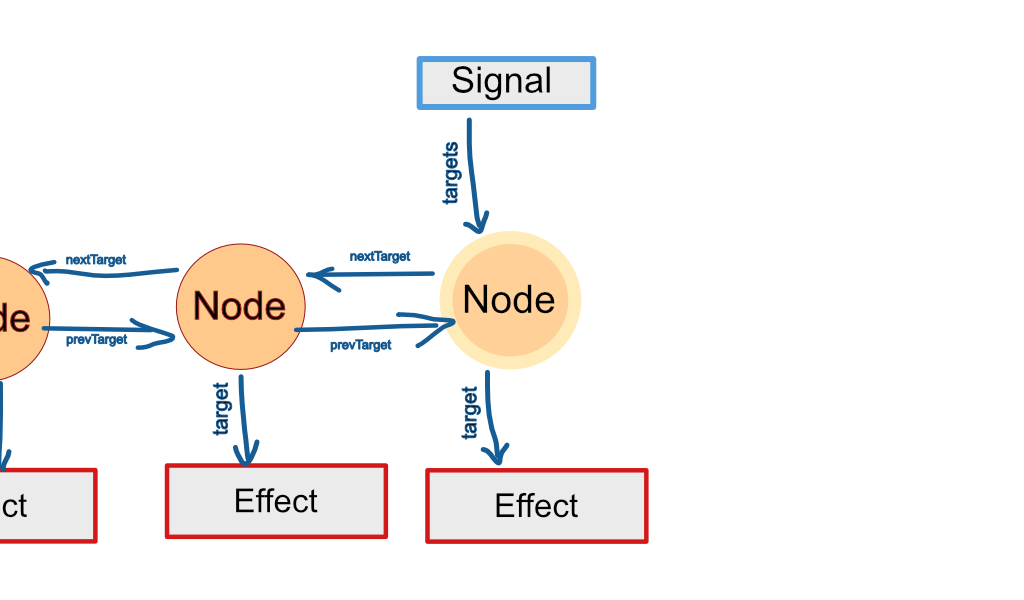

Now let's do the same the other way around: For each dependent create a "target Node". The Node's target attribute points to the dependent effect or computed signal. nextTarget and prevTarget build a doubly linked list. Plain and computed signal get a targets attribute pointing to the first target Node in their dependent list.

But hey, dependencies and dependents come in pairs. For every source Node there must be a corresponding target Node. We can exploit this fact and smush "source Nodes" and "target Nodes" into just "Nodes". Each Node becomes a sort of quad-linked monstrosity that the dependent can use as a part of its dependency list, and vice versa.

Each Node can have additional stuff attached to it for bookkeeping purposes. Before each compute/effect function we iterate through the previous dependencies and set the "unused" flag of each Node. We also temporarily store the Node to its .source.node property for later. The function can then start its run.

During the run, each time a dependency is read, the bookkeeping values can be used to discover whether that dependency has already been seen during this or the previous run. If the dependency is from the previous run, we can recycle its Node. For previously unseen dependencies we create new Nodes. The Nodes are then shuffled around to keep them in reverse order of use. At the end of the run we walk through the dependency list again, purging Nodes that are still hanging around with the "unused" flag set. Then we reverse the list of remaining nodes to keep it all neat for later consumption.

This delicate dance of death allows us to allocate only one Node per each dependency-dependent pair and then use that Node indefinitely as long as the dependency relationship exists. If the dependency tree stays stable, memory consumption also stays effectively stable after the initial build phase. All the while dependency lists stay up to date and in order of use. With a constant O(1) amount of work per Node. Nice!

Eager Effects

With the dependency tracking taken care of, eager effects are relatively straightforward to implement via change-notifications. Signals notify their dependents about value changes. If the dependent itself is a computed signal that has dependents, then it passes the notification forward, and so on. Effects that get a notification schedule themselves to be run.

We added a couple of optimizations here. If the receiving end of a notification has already been notified before, and it hasn't yet had a chance to run, then it won't pass the notification forward. This mitigates cascading notification stampedes when the dependency tree fans out or in. Plain signals also don't notify their dependents if the signal's value doesn't actually change (e.g. s.value = s.value). But that's just being polite.

For effects to be able to schedule themselves there needs to be some sort of a list of scheduled effects. We added an dedicated attribute .nextBatchedEffect to each Effect instance, letting Effect instances do double duty as nodes in a singly-linked scheduling list. This reduces memory churn, because scheduling the same effect again and again requires no additional memory allocations or deallocations.

Interlude: Notification Subscriptions vs. GC

We haven't been completely truthful. Computed signals don't actually always get notifications from their dependencies. A computed signal subscribes to dependency notifications only when there's something, like an effect, listening to the signal itself. This avoids problems in situations like this:

const s = signal(0);

{

const c = computed(() => s.value);

}

// c has gone out of scopeWere c to always subscribe to notifications from s, then c couldn't get garbage collected until s too falls out of scope. That's because s would keep hanging on to a reference to c.

There are multiple solutions to this problem, like using WeakRefs or requiring computed signals to be manually disposed. In our case linked lists provide a very convenient way to dynamically subscribe and unsubscribe to dependency notifications on the fly, thanks to all that O(1) stuff. The end result is that you don't have to pay any special attention to dangling computed signal references. We felt this was the most ergonomic and performant approach.

In those cases where a computed signal has subscribed to notifications we can use that knowledge for extra optimizations. This brings us to laziness & caching.

Lazy & Cached Computed Signals

The easiest way to implement a lazy computed signal would be to just recompute each time its value is read. It wouldn't be very efficient, though. That's where caching and dependency tracking help a bunch.

Each plain and computed signal has their own version number. They increment their version numbers every time they've noticed their own value change. When a compute function is run, it stores in the Nodes the last seen version numbers of its dependencies. We could have chosen to store the previous dependency values in the nodes instead of version numbers. However, since computed signals are lazy, they could therefore hang on to outdated and potentially expensive values indefinitely. So we felt version numbering was a safe compromise.

We ended up with the following algorithm for figuring out when a computed signal can take the day off and reuse its cached value:

- If the no signal anywhere has changed values since the last run, then bail out & return the cached value.

Each time a plain signal changes it also increments a global version number, shared between all plain signals. Each computed signal keeps track of the last global version number they've seen. If the global version hasn't changed since last computation, then recomputation can be skipped early. There couldn't be any changes to any computed value anyway in that case.

- If the computed signal is listening to notifications, and hasn't been notified since the last run, then bail out & return the cached value.

When a computed signal gets a notification from its dependencies, it flags the cached value as outdated. As described earlier, computed signals don't always get notifications. But when they do we can take advantage of it.

- Re-evaluate the dependencies in order. Check their version numbers. If no dependency has changed its version number, even after re-evaluation, then bail out & return the cached value.

This step is the reason why we gave special love and care to keeping dependencies in their order of use. If a dependency changes, then we don't want to re-evaluate dependencies coming later in the list because it might just be unnecessary work. Who knows, maybe the change in that first dependency causes the next compute function run to drop the latter dependencies.

- Run the compute function. If the returned value is different from the cached one, then increment the computed signal's version number. Cache and return the new value.

This is the last resort! But at least if the new value is equal to the cached one, then the version number won't change, and the dependents down the line can use that to optimize their own caching.

The last two steps often recurse into the dependencies. That's why the earlier steps are designed to try to short-circuit the recursion.

Endgame

In typical Preact fashion there were multiple smaller optimizations thrown in along the way. The source code contains some comments that may or may not be useful. Check out the tests if you're curious about what kinds of corner cases we came up with to ensure our implementation is robust.

This post was a brain dump of sorts. It outlined the main steps we took to make @preact/signals-core version 1.2.0 better - to some definition of "better". Hopefully some of the ideas listed here will resonate, and get reused and remixed by others. At least that's the dream!

Huge thanks to everyone who contributed. And thanks to you for reading this far! It's been a trip.